Historical Collection Woolworth’s Counter Replica Honors Civil Rights Pioneers

By Meredith Collins

For many of us, “history” seems so far away, something we learned about in school or read about in a textbook. The Statesville Historical Collection’s recreation of the F. W. Woolworth counter brings history home to a very pivotal event in the Civil Rights Movement that happened right here in Statesville, NC with community members still well-known today.

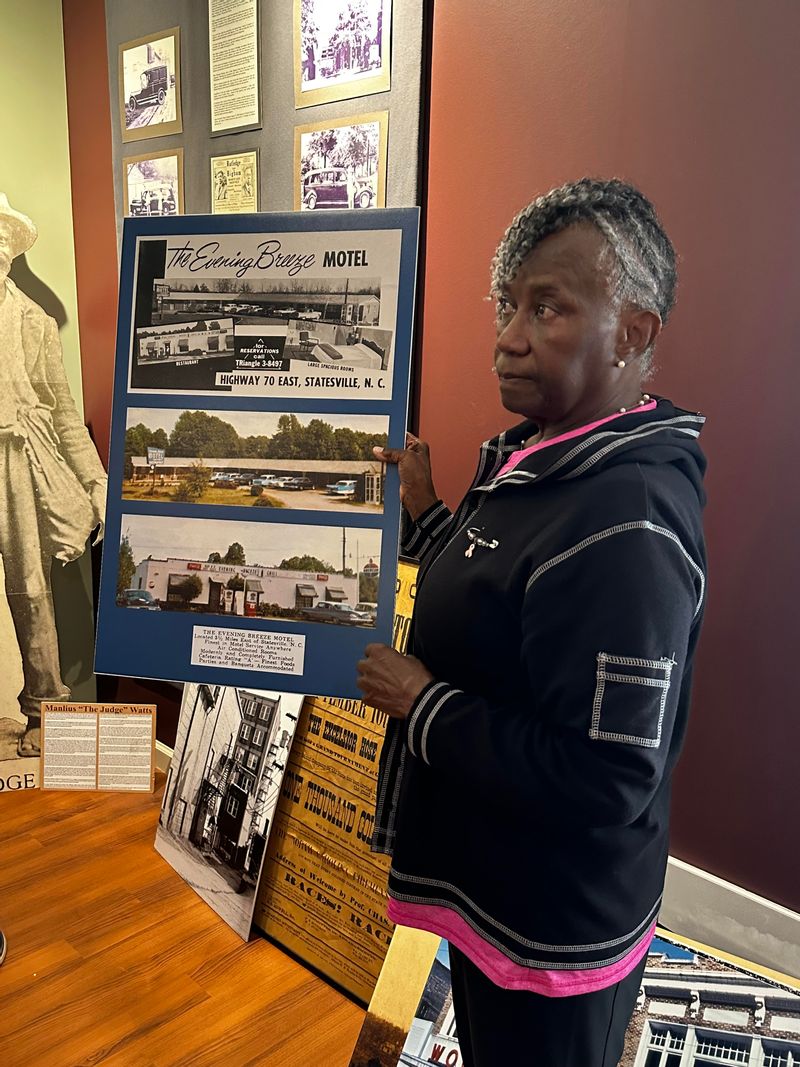

Interestingly enough, during renovations of The Holland Building (117 South Center Street, Downtown Statesville) to make it the new home of the Statesville Historical Collection, they discovered an entire section of original tile still remaining from when the building was a Woolworths decades ago. A new wall had just been built right over it. Of course, that sparked local collector and proprietor of the Statesville Historical Collection, Dr. Steve Hill, to do a little demo and recreate the original counter to tell the story of how Statesville was involved in the Civil Rights Movement. The powerful display includes original bar stools, photos and menus. A mirror behind allows visitors to “reflect” on what it means to take a stand for something they believe in.

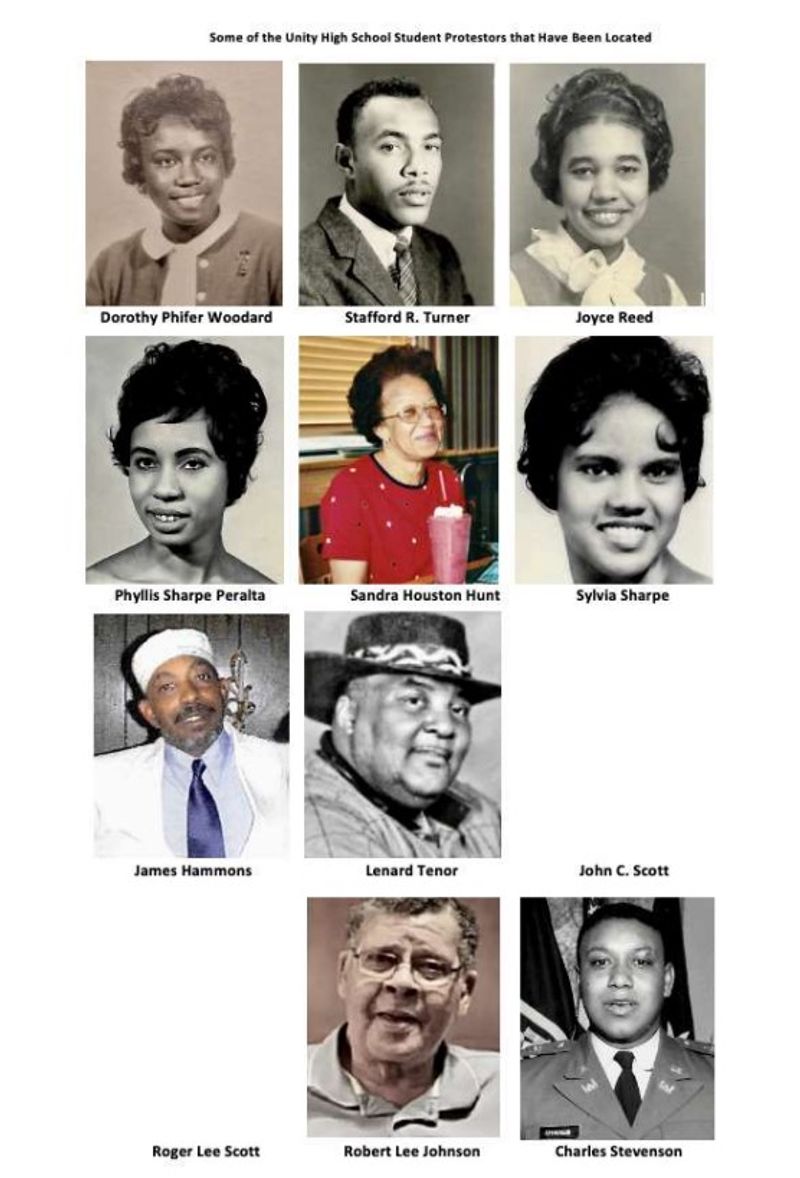

Andre Nabors, Visit NC Partner Relations Manager; Kim Wasson, Statesville City Councilwoman; Dorothy Woodard, Woolworth's Sit-In Protestor; and Steve Hill, local historian and proprietor of the Statesville Historical Collection at the replica of the F.W. Woolworth's Counter back in the 1960s. Sit-ins at this location started the Civil Rights Movement in Statesville, NC.

“It’s been an eye-opening experience to hear the stories of Dorothy Woodard and James Hammons,” Dr. Hill said. “I was just a 6-year-old at the time. We read about it, we know about the Greensboro sit-in, but most people don’t realize we had our own right here in Statesville. I think it’s long overdue that we do something for those Civil Rights pioneers right here in our own community.”

One of those pioneers is Dorothy Woodard. As a 14-year-old student, Dorothy joined the civil rights sit-in protest at the Woolworth’s counter in Statesville in March 1960. At this time, African Americans could shop in the Woolworth’s store in downtown Statesville, but the lunch counter was “Whites Only”. On February 1, 1960, four African Americans sat at the lunch counter at the Woolworth’s in Greensboro, starting a movement that would ripple across the south and inspire sit-ins in 55 cities.

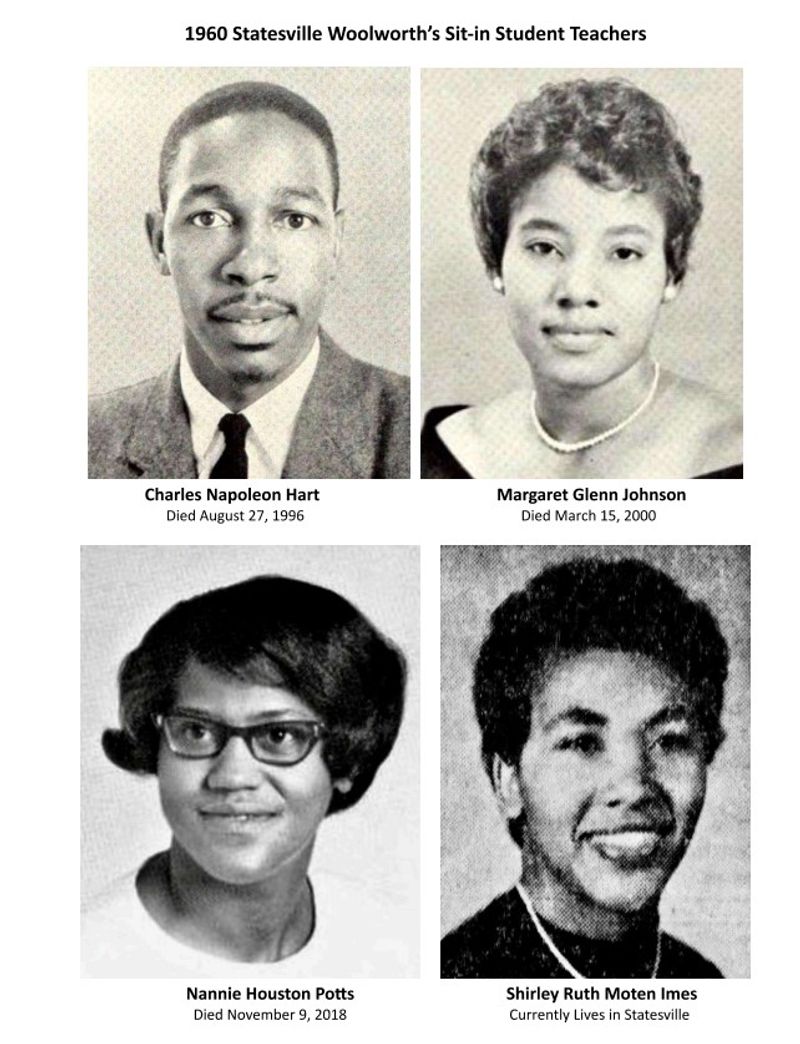

On March 15, 1960, Statesville had their first sit-in at the Woolworth’s Counter. Four student teachers from the Unity School (Charles Hart, Margaret Glenn Johnson, Nannie Houston Potts and Shirley Ruth Moten Imes) sat at the Woolworth’s Counter for 45 minutes before being escorted out by local police. After the sit-in, the student teachers were transferred back to their local colleges and sent to other schools. They were later charged with trespassing and fined. Locals were determined not to let the movement stop there. News of the demonstration spread, and crowds gathered around the store. Later that evening, acts of violence erupted with African Americans in the community targeted and rocks thrown through their windows.

Life During Segregation

Growing up during segregation, Dorothy recalls how education was supposed to be “separate but equal” but she says it was very far from equal.

A Future in Education

Dorothy was teaching at Oakwood Junior High School in 1969 during desegregation. “The kids were reassigned to different schools after Christmas,” she said. “The school board realized that all facilities were not equal, and they shut down the little black schools in the communities.”

Dorothy says desegregation was a very tense time in the schools. She took a short break from education because of the tense times, but then returned and ended up teaching at West Rowan High School for 24 years. Later, she was an assistant principal at Knox Middle School and then served as principal in Newton Conover City Schools. She remains involved in the Iredell-Statesville School system still today.

Dorothy continues to educate students and the community about segregation by telling her story.

“When I walked in and saw what Steve was planning, I was overwhelmed,” Dorothy said. “It’s so important to tell the story – if you don’t know the history, you’re doomed to repeat it. So many things are happening right now that could cause it to be repeated.”

Dorothy presses on to champion for equal rights for all.

The Statesville Historical Collection is located in The Holland Building at 117 South Center St, Downtown Statesville and will be open for visitors in December. Visit www.statesvillehistory.com for more information.